Java Concurrency at Scale: Migrating from Thread Pools to Virtual Threads

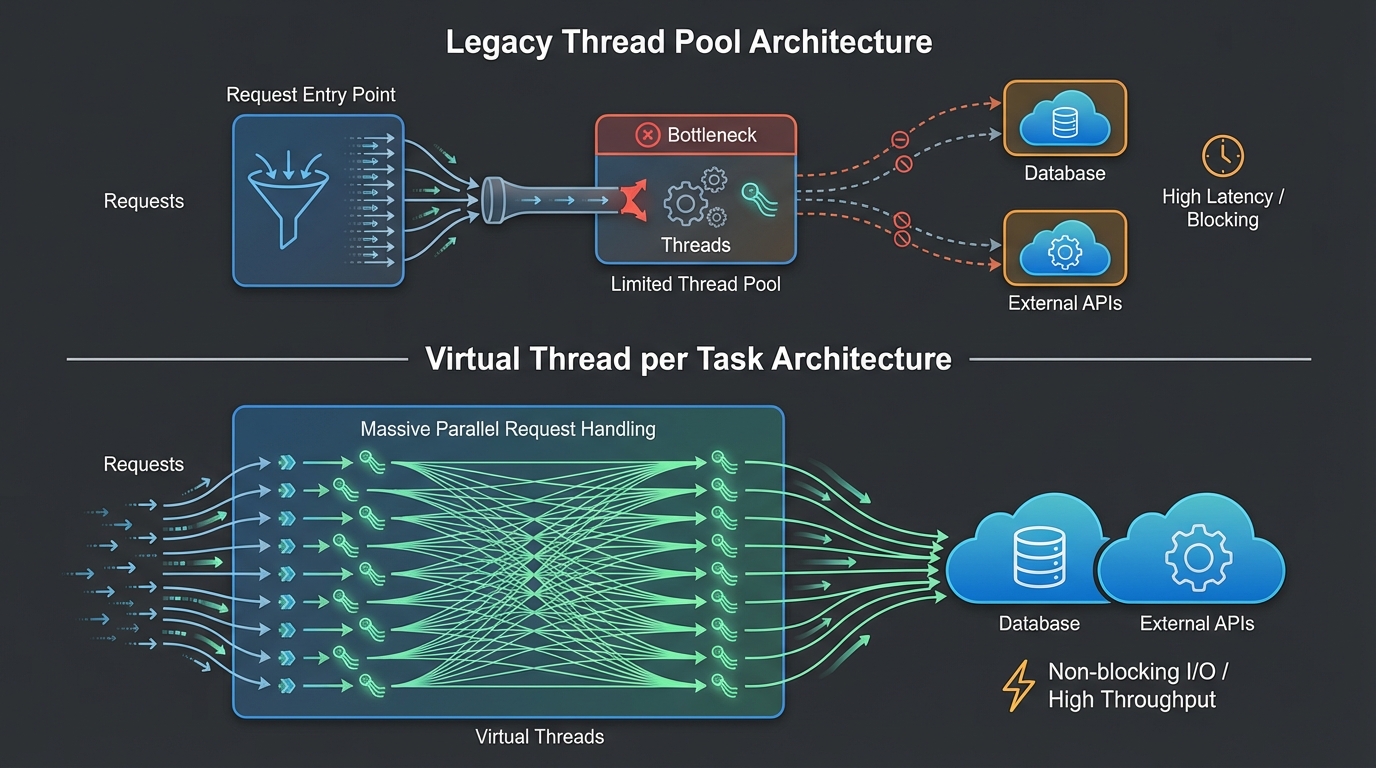

For the better part of two decades, Java concurrency has been a negotiation with the Operating System. We built high-throughput systems on the back of the “One-Thread-Per-Request” model, eventually hitting the hard ceiling of OS resource limits. We patched this with thread pools, and when that wasn’t enough, we twisted our code into complex, reactive pretzels using asynchronous frameworks to squeeze every ounce of CPU out of blocking I/O.

With the release of Project Loom and Virtual Threads (standardized in Java 21), the negotiation has changed. We no longer have to choose between the simplicity of synchronous code and the scalability of asynchronous non-blocking I/O. However, migrating to this paradigm isn’t just about changing an ExecutorService. It requires a fundamental shift in how we understand resource management, the Java Memory Model (JMM), and thread lifecycles.

In this deep dive, we will move beyond the “Hello World” of Virtual Threads. We will dissect the architectural implications, refactor complex CompletableFuture chains, analyze the impact on the JMM, and provide a concrete guide for migrating high-load systems.

The Evolution: From OS Wrappers to User-Mode Threads

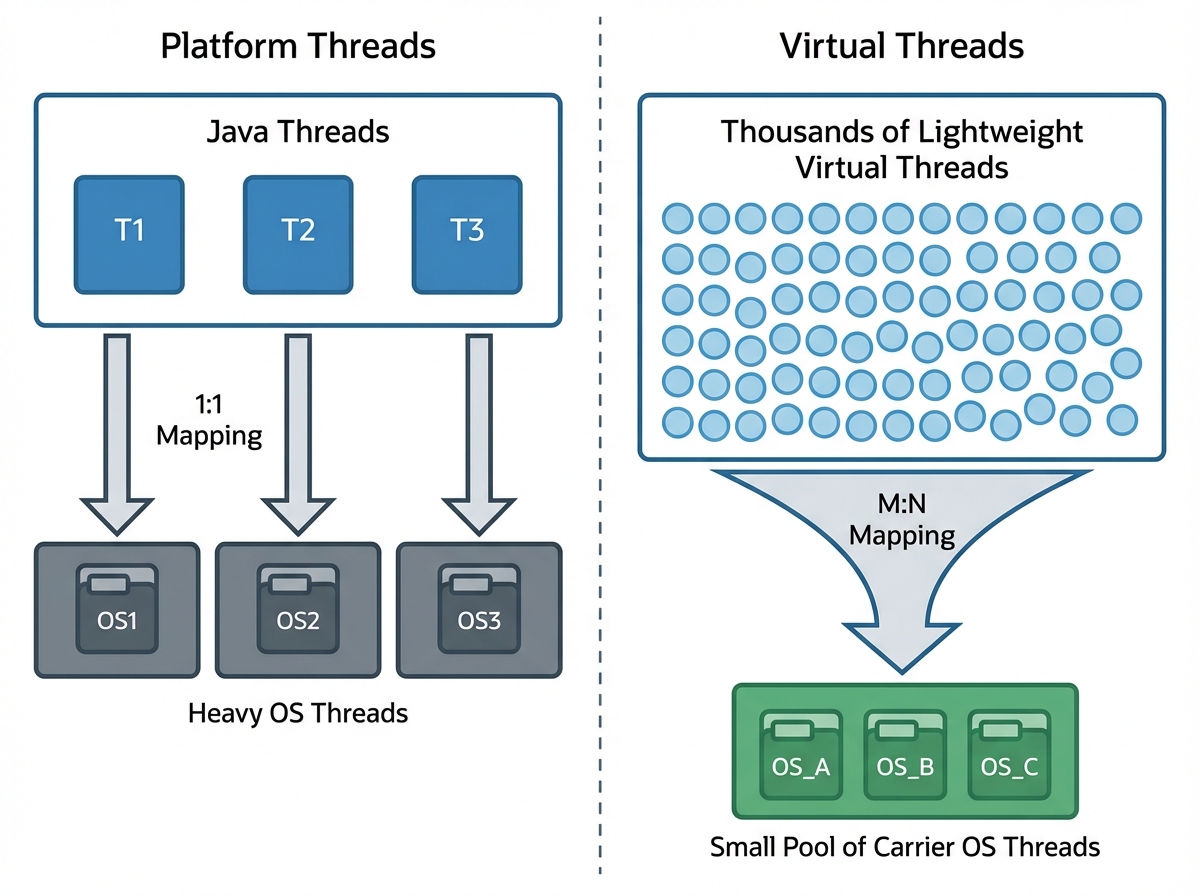

To understand why Virtual Threads are revolutionary, we must acknowledge the cost of the Platform Thread. A traditional Java Thread is a thin wrapper around an OS kernel thread.

The Cost of Platform Threads

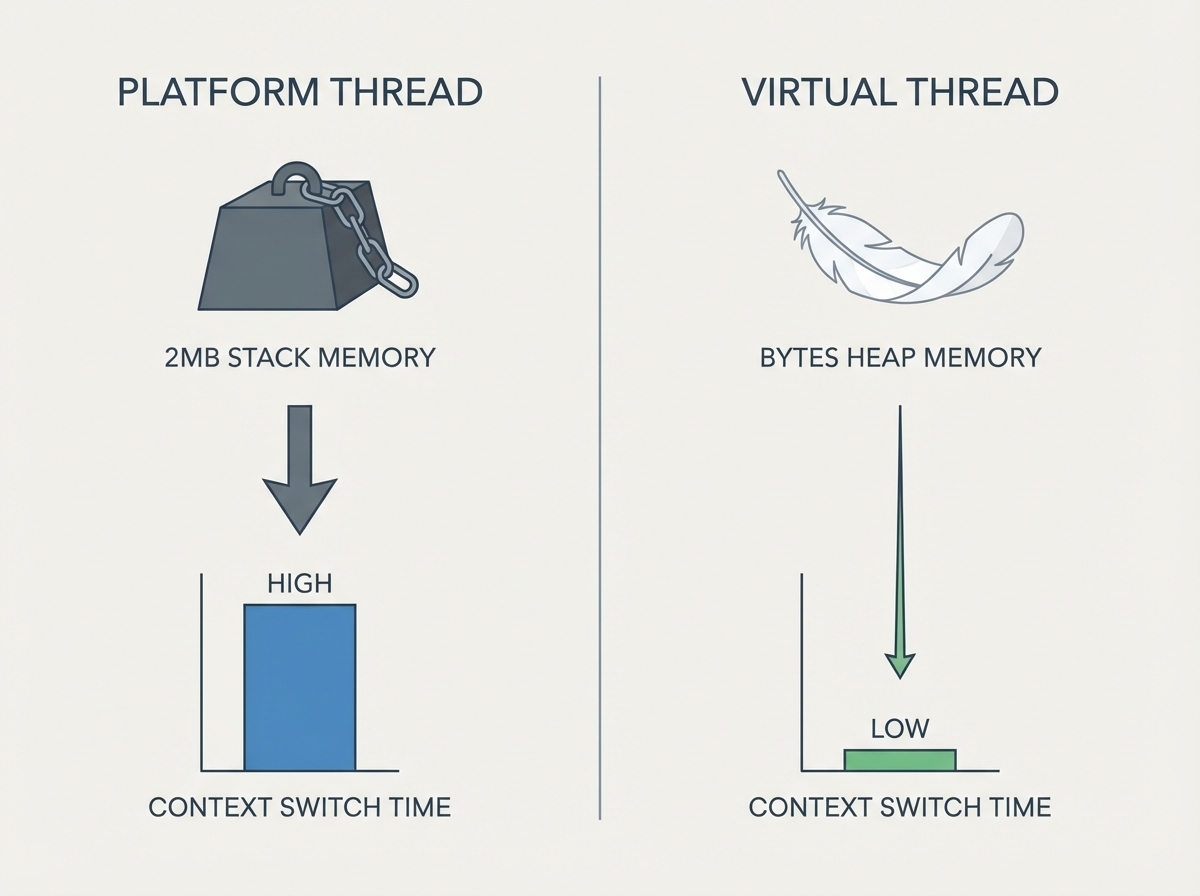

- Stack Size: OS threads typically reserve ~1MB - 2MB of stack memory. Spawning 100,000 threads immediately demands ~200GB of RAM, regardless of actual usage.

- Context Switching: Switching between kernel threads involves a round-trip to the OS scheduler. This context switch is computationally expensive (cache pollution, TLB flushes).

- Scheduling Granularity: The OS scheduler is designed for general-purpose computing, not specifically for Java’s runtime behavior.

The Virtual Thread Paradigm

Virtual Threads are user-mode threads scheduled by the JVM, not the OS. They are mapped M:N onto Platform Threads (called “carrier threads”).

- Footprint: A virtual thread’s stack lives in the Java heap and grows dynamically. It can be as small as a few hundred bytes.

- Scheduling: The JVM handles the mounting and unmounting of virtual threads onto carrier threads. This operation is barely more expensive than a function call.

This shift allows us to return to the “One-Thread-Per-Task” style without the resource penalty.

Blocking I/O: The Secret Sauce

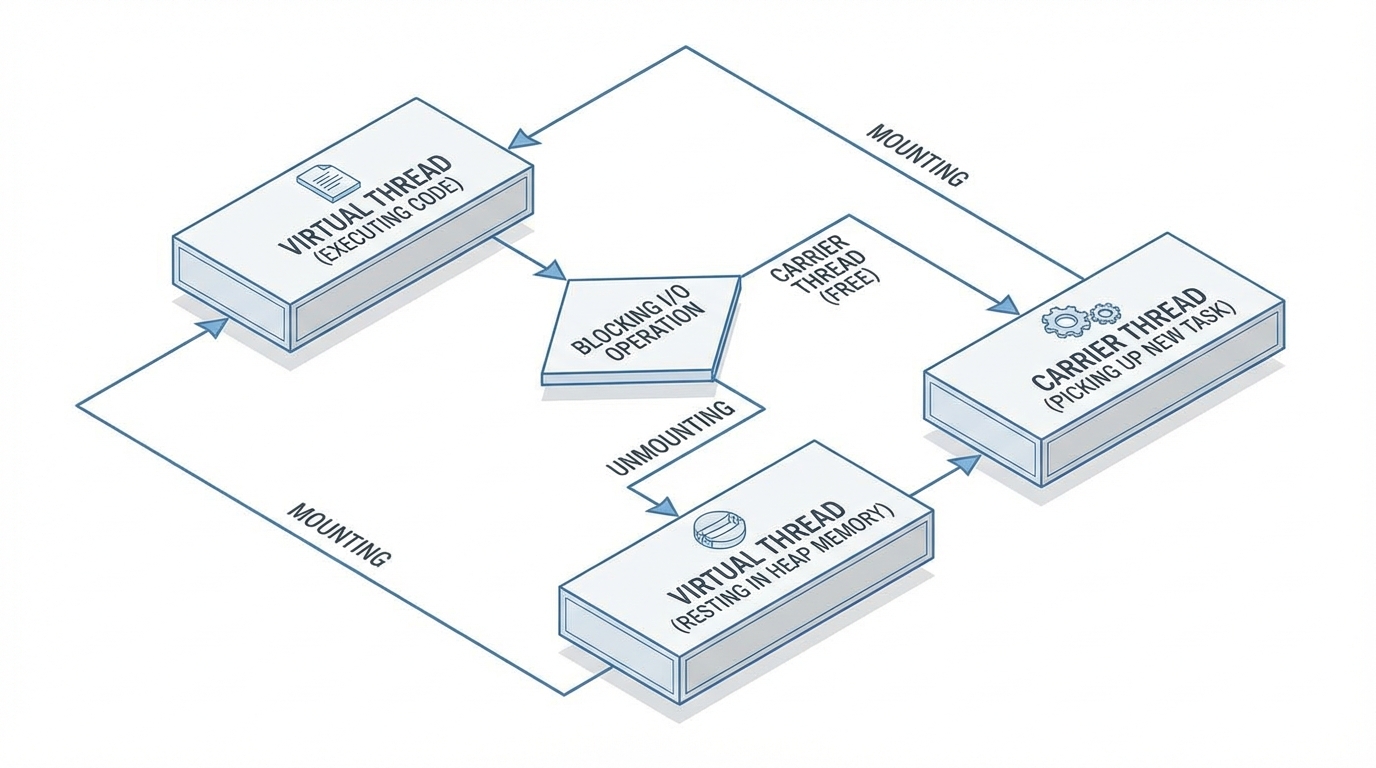

The magic of Virtual Threads lies in how they handle blocking operations. In the Platform Thread model, a blocking call (like reading from a Socket or a Database) halts the OS thread. The CPU core sits idle (or forces a context switch) while waiting for bytes to arrive.

With Virtual Threads, the java.util.concurrent libraries have been rewritten. When a virtual thread performs a blocking I/O operation:

- The JVM detects the blocking call.

- It unmounts the virtual thread from the carrier thread.

- The virtual thread’s stack is parked in the heap.

- The carrier thread is arguably instantly free to execute another virtual thread.

- When the I/O completes, the OS signals the JVM (usually via epoll/kqueue), and the virtual thread is rescheduled (mounted) onto an available carrier.

Code Comparison: The Throughput Test

Let’s look at a scenario simulating a high-latency network call.

Traditional Thread Pool Approach:

import java.util.concurrent.Executors;

import java.util.concurrent.TimeUnit;

public class PlatformThreadServer {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Limited by OS resources.

// 10,000 threads might crash a smaller container.

try (var executor = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(200)) {

for (int i = 0; i < 10_000; i++) {

executor.submit(() -> {

try {

// Simulating 500ms Database Latency

TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS.sleep(500);

System.out.println("Task completed by: " + Thread.currentThread());

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

}

});

}

}

}

}

In the code above, we cap the pool at 200. If 10,000 requests come in, 9,800 are queued. Latency spikes.

Virtual Thread Approach:

import java.util.concurrent.Executors;

import java.util.concurrent.TimeUnit;

public class VirtualThreadServer {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// No pool limits needed. Creates a new virtual thread per task.

try (var executor = Executors.newVirtualThreadPerTaskExecutor()) {

for (int i = 0; i < 1_000_000; i++) { // Scale to 1 Million

executor.submit(() -> {

try {

// The Carrier Thread is released during this sleep

TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS.sleep(500);

// Note: toString() will show the virtual thread and carrier

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

}

});

}

}

}

}

Here, we can submit 1 million tasks. The JVM will likely use only as many carrier threads as there are CPU cores (e.g., 12 threads on a 12-core machine). The throughput is vastly superior because the threads are not holding onto OS resources while waiting.

Resource Efficiency Analysis

The implications for hardware utilization are massive. Under the traditional model, scaling meant adding more RAM to support thread stacks. With Virtual Threads, scaling is bound primarily by CPU cycles and Heap space for application data.

This changes capacity planning. In a microservices architecture, services that are I/O bound (like API Gateways or BFFs) can see a footprint reduction of 50-80% while handling higher concurrency.

Refactoring Async Workflows: Killing the CompletableFuture

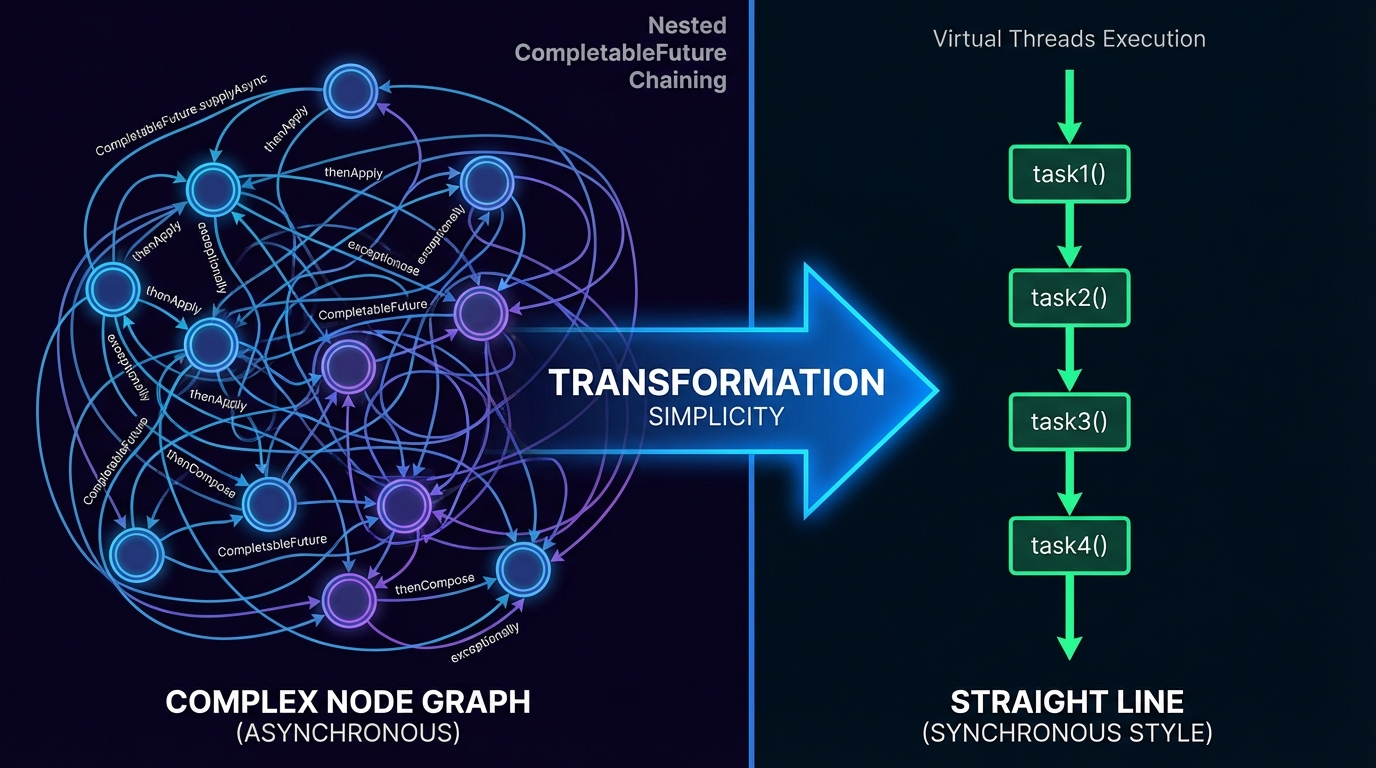

Between Java 8 and Java 21, the industry adopted CompletableFuture and Reactive frameworks (RxJava, Reactor) to bypass the thread-per-request limitations. While effective, this introduced:

- Cognitive Load: “Callback Hell” or complex chaining.

- Loss of Context: Stack traces become useless because the exception happens in a different thread than the caller.

- Debugging Difficulties: You can’t step-debug easily through a reactive chain.

Virtual Threads allow us to write imperative, synchronous-looking code that runs asynchronously under the hood.

Scenario: The Aggregation Service

Imagine an endpoint that fetches User details, then fetches their Orders, and essentially their Loyalty points, combining them all.

The CompletableFuture Nightmare:

public CompletableFuture<UserDashboard> getDashboardAsync(String userId) {

return getUser(userId)

.thenCompose(user ->

getOrders(user.getId())

.thenCombine(getLoyalty(user.getId()), (orders, loyalty) -> {

return new UserDashboard(user, orders, loyalty);

})

).exceptionally(ex -> {

log.error("Async chain failed", ex);

return new UserDashboard(); // Fallback

});

}

This code is brittle. If getUser fails, the stack trace won’t easily tell you where the request originated.

The Virtual Thread Refactor (Structured Concurrency):

We can revert to a clean, sequential style. For parallel execution (fetching orders and loyalty simultaneously), we use the new StructuredTaskScope (preview in 21, maturing in later versions) or standard ExecutorServices.

// Using standard Executors with Virtual Threads

public UserDashboard getDashboardVirtual(String userId) throws ExecutionException, InterruptedException {

try (var executor = Executors.newVirtualThreadPerTaskExecutor()) {

// 1. Fetch User (Sequential)

User user = getUser(userId); // Blocking, but cheap!

// 2. Fetch Orders and Loyalty (Parallel)

var ordersFuture = executor.submit(() -> getOrders(user.getId()));

var loyaltyFuture = executor.submit(() -> getLoyalty(user.getId()));

// 3. Aggregate

// The .get() calls block the virtual thread, releasing the carrier.

return new UserDashboard(user, ordersFuture.get(), loyaltyFuture.get());

}

}

This code is readable, debuggable, and performs just as well (if not better) than the reactive version. The stack trace upon exception will show the exact line number in getDashboardVirtual.

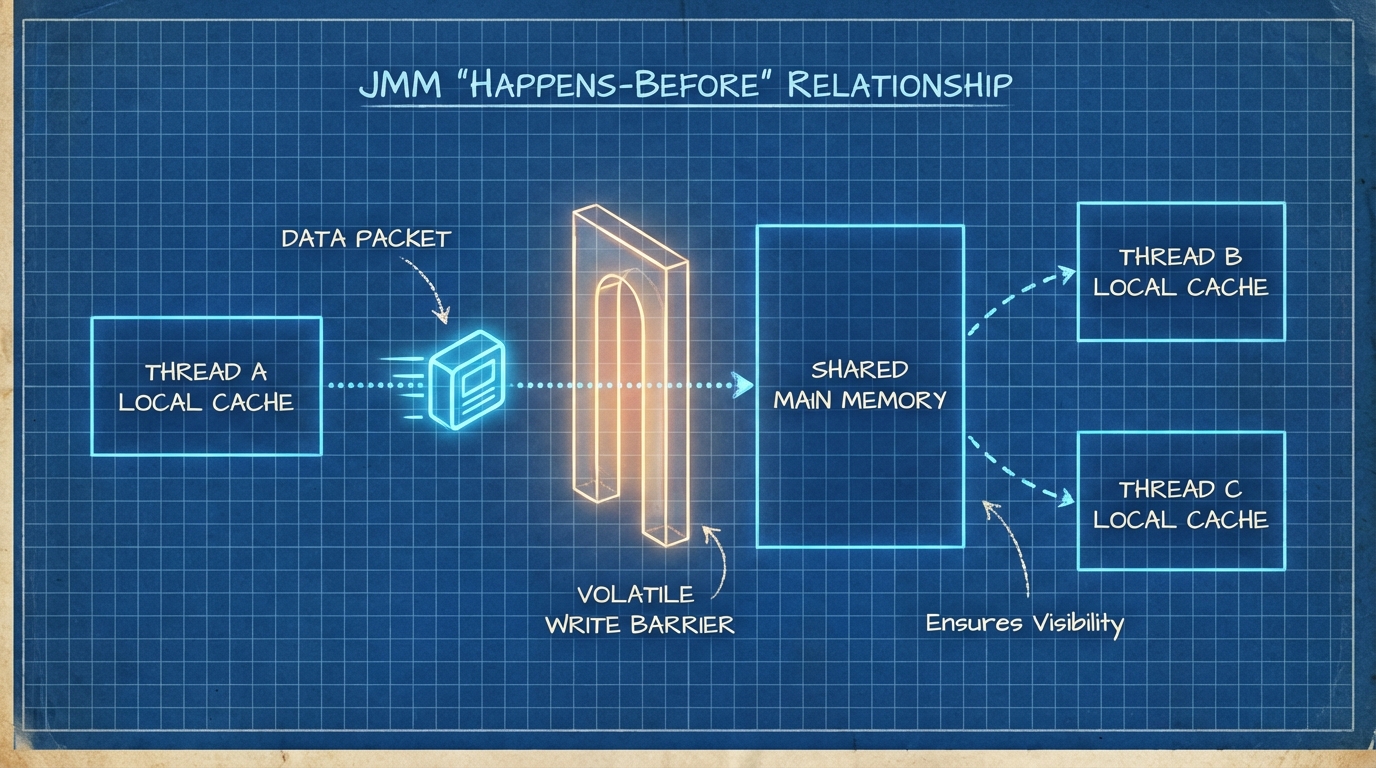

The Java Memory Model (JMM) & Happens-Before

One common misconception is that Virtual Threads change the Java Memory Model. They do not. The rules of visibility, atomicity, and ordering remain identical. However, the implications of shared state change because you now have millions of threads potentially contending for resources.

The Happens-Before Relationship

Just like platform threads:

- Actions in a thread prior to

Thread.start()happen-before any actions in the started thread. - Actions in a thread happen-before

Thread.join()returns. - Writing a volatile variable happens-before reading it.

The Pitfall: Thread-Locals

In the era of thread pools, ThreadLocal was often used as a request-scoped cache (e.g., holding a Transaction Context or User ID).

- Old World: 200 Threads = 200 ThreadLocal maps. Manageable.

- New World: 1,000,000 Virtual Threads = 1,000,000 ThreadLocal maps. Heap Exhaustion.

Migration Tip: Avoid ThreadLocal with Virtual Threads. Use explicit parameter passing or specialized ScopedValue (JEP 429) designed for this exact purpose.

Managing Shared State: Locking and Pinning

This is the most critical technical nuance in the migration.

The “Pinning” Problem

A virtual thread is “pinned” to its carrier thread if:

- It executes a

synchronizedblock or method. - It executes a native method (JNI).

When pinned, if the virtual thread performs a blocking operation, it blocks the underlying carrier thread. This reintroduces the scalability bottleneck.

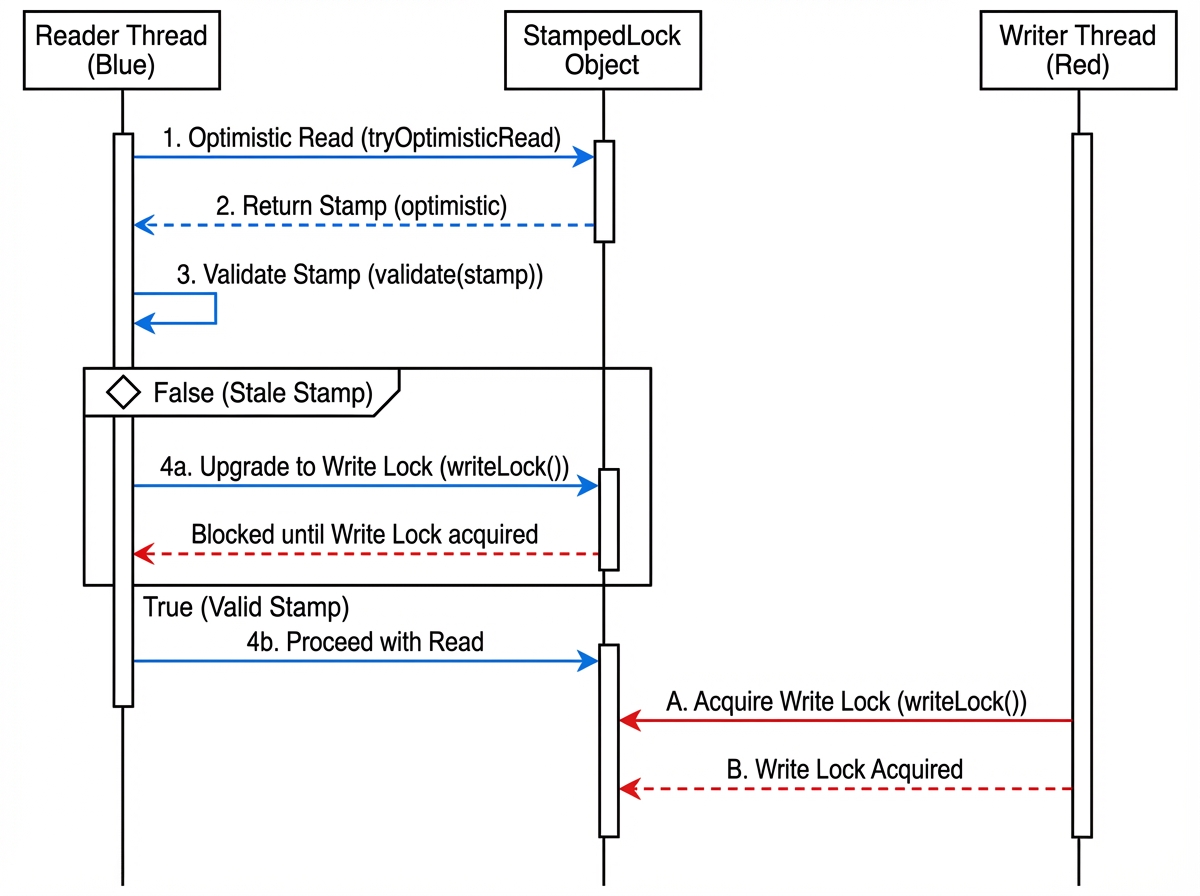

The Solution: ReentrantLock and StampedLock

To avoid pinning, replace synchronized blocks with ReentrantLock where possible, as the JDK’s virtual thread scheduler is aware of j.u.c locks and can unmount threads waiting on them.

For high-concurrency read-heavy scenarios, StampedLock offers optimistic locking, which is significantly faster and aligns well with the high volume of virtual threads.

High-Performance Counter Example:

import java.util.concurrent.locks.StampedLock;

public class HighThroughputState {

private double x, y;

private final StampedLock sl = new StampedLock();

// Optimistic Read - Excellent for high concurrency virtual threads

public double distanceFromOrigin() {

long stamp = sl.tryOptimisticRead();

double currentX = x, currentY = y;

// Check if a write occurred while we were reading

if (!sl.validate(stamp)) {

// Fallback to read lock

stamp = sl.readLock();

try {

currentX = x;

currentY = y;

} finally {

sl.unlockRead(stamp);

}

}

return Math.sqrt(currentX * currentX + currentY * currentY);

}

public void move(double deltaX, double deltaY) {

long stamp = sl.writeLock();

try {

x += deltaX;

y += deltaY;

} finally {

sl.unlockWrite(stamp);

}

}

}

By using StampedLock, we avoid synchronized (preventing pinning) and reduce contention overhead compared to standard ReentrantReadWriteLock.

Migration Guide: From Pools to Virtual

Migrating a legacy application requires a strategic approach. You cannot simply flip a switch if you rely heavily on synchronized or thread-local caches.

Step 1: Dependency Audit

Identify libraries that synchronize on I/O. Older JDBC drivers or XML parsers might do this. Upgrade dependencies to versions that declare “Virtual Thread Friendliness” (usually by replacing synchronized with ReentrantLock).

Step 2: Stop Pooling Threads

Anti-Pattern:

// DON'T DO THIS

ExecutorService pool = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(100, Thread.ofVirtual().factory());

Pooling virtual threads defeats their purpose. They are disposable. Always use:

ExecutorService executor = Executors.newVirtualThreadPerTaskExecutor();

Step 3: Bound External Resources

While you can create infinite threads, you cannot create infinite Database Connections.

- Keep the Connection Pool: HikariCP or similar DB pools are still mandatory.

- Mechanism: When 10,000 virtual threads ask for a connection, 9,900 will park efficiently. The bottleneck moves from the Server CPU to the Database. This is desired behavior; the application server is no longer the weak link.

Step 4: Spring Boot Configuration

If you are on Spring Boot 3.2+, enabling virtual threads is configuration-driven:

spring:

threads:

virtual:

enabled: true

This automatically configures Tomcat/Jetty to use a virtual thread executor for incoming HTTP requests.

Step 5: Handling “Pinning” in Logs

Run your application with -Djdk.tracePinnedThreads=full. This will print stack traces whenever a virtual thread blocks while pinned. Refactor these hotspots specifically.

Conclusion

Migrating to Virtual Threads is the most significant shift in Java concurrency since Java 5. It allows us to build high-throughput applications that are easier to write, read, and debug.

However, it is not a magic bullet that fixes bad architecture. It exposes bottlenecks downstream (databases, external APIs) and requires disciplined management of shared state. By moving away from synchronized toward ReentrantLock and StampedLock, and by abandoning the concept of thread pooling for task execution, you can unlock the full potential of modern hardware.

The era of the “One-Thread-Per-Request” is back—but this time, it scales.