Escaping the if (isAdmin) Trap: Implementing Scalable RBAC and ABAC in Node.js

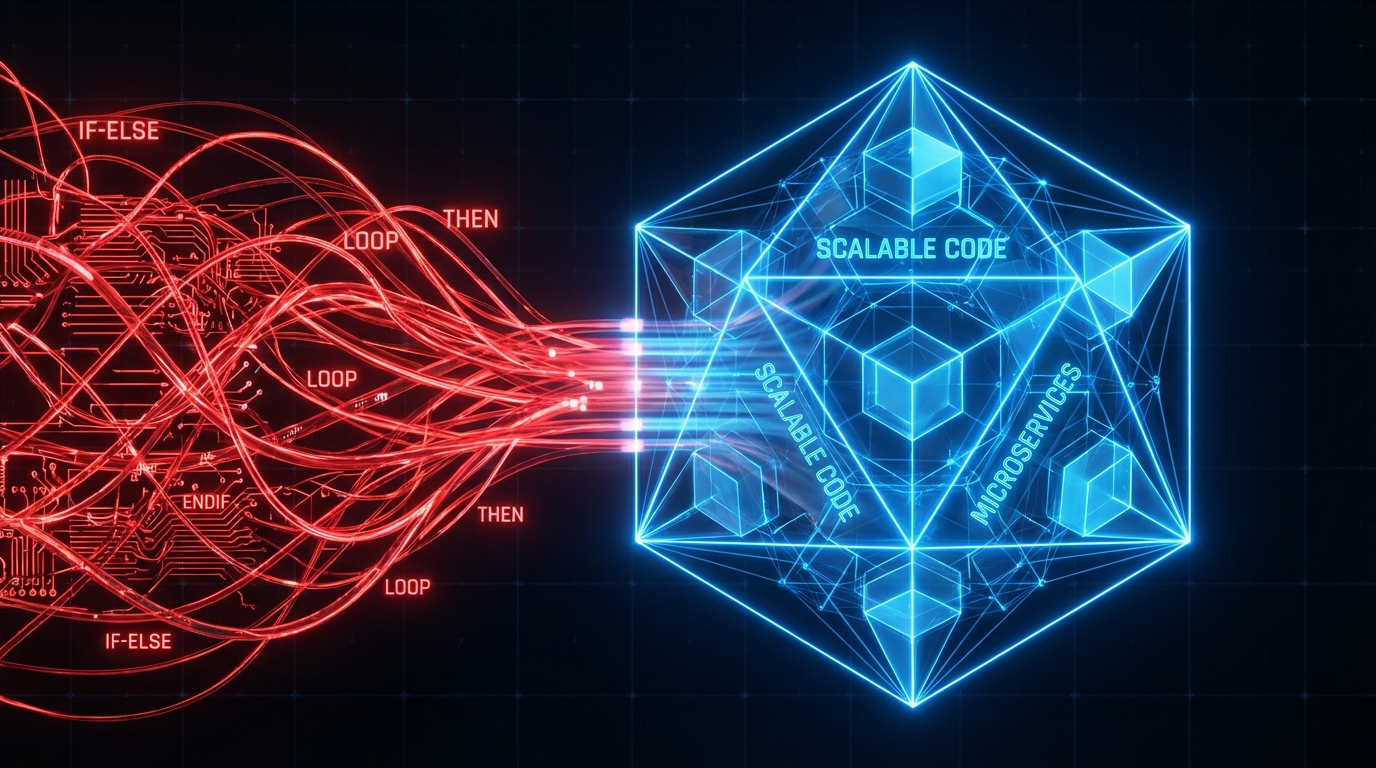

We have all written it. The line of code that marks the beginning of the end for a scalable codebase:

if (user.isAdmin || (user.role === 'manager' && resource.ownerId === user.id)) {

// Allow logic

}

It starts innocently enough. A boolean flag here, a string check there. But as your application grows, these conditionals metastasize. Suddenly, you have “SuperAdmins” who need to see everything, “Editors” who can publish but not delete, and “Viewers” who can only see resources within their specific organization.

The conditionals scatter across controllers, services, and even view layers. When a security audit requests a change to the “Editor” role, you are forced to grep through hundreds of files, hoping you didn’t miss a nested if statement.

This is the “Boolean Trap.” It is brittle, untestable, and insecure by design.

In this deep dive, we are going to dismantle this pattern. We will architect a robust, database-driven authorization system in Node.js that transitions from simple Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) to granular Attribute-Based Access Control (ABAC). We will cover hierarchical inheritance, ownership policies, reusable middleware, and the caching strategies required to keep it performant.

The Evolution: From Boolean Flags to ABAC

To solve authorization at scale, we must decouple who the user is (Identity) from what they are allowed to do (Authorization).

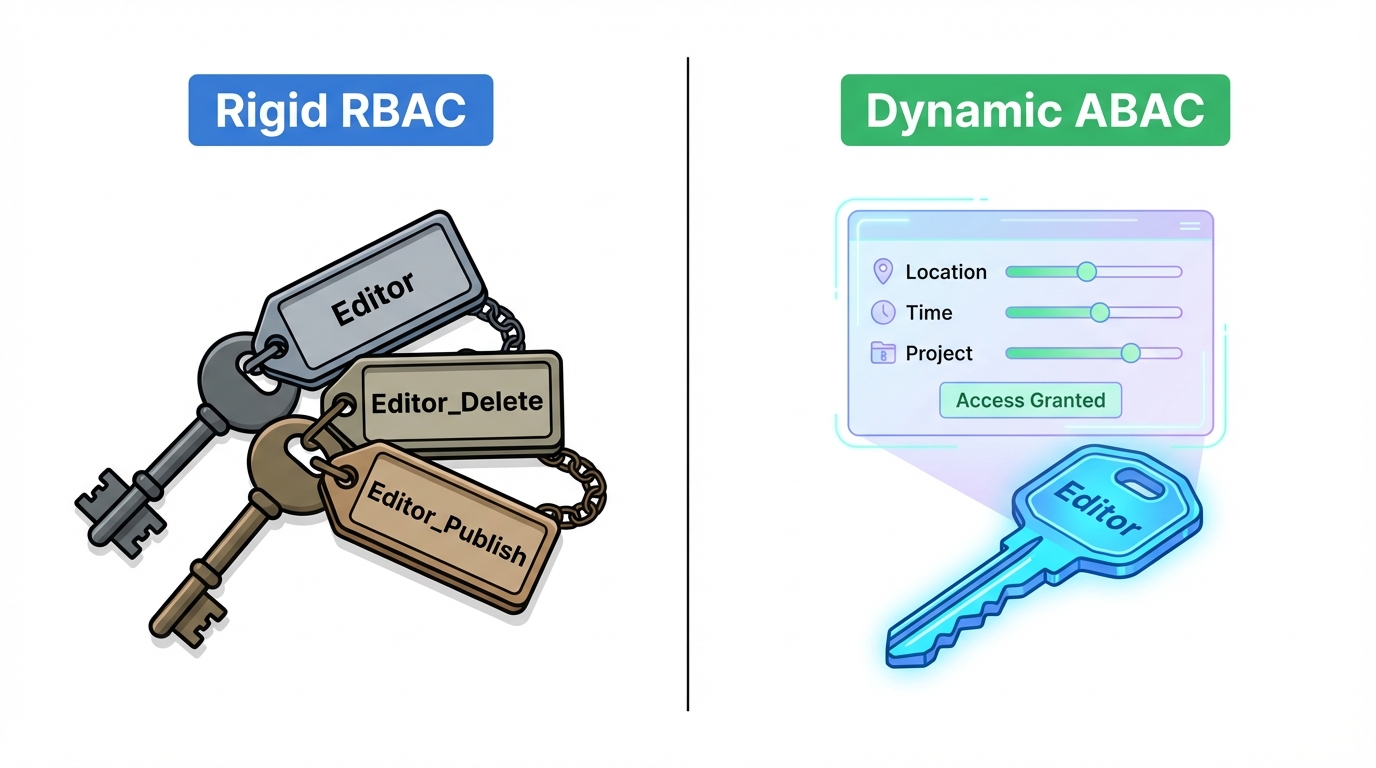

- RBAC (Role-Based Access Control): You are an “Admin.” Therefore, you can do “Admin things.” This works for coarse-grained access but fails when rules depend on the state of the data.

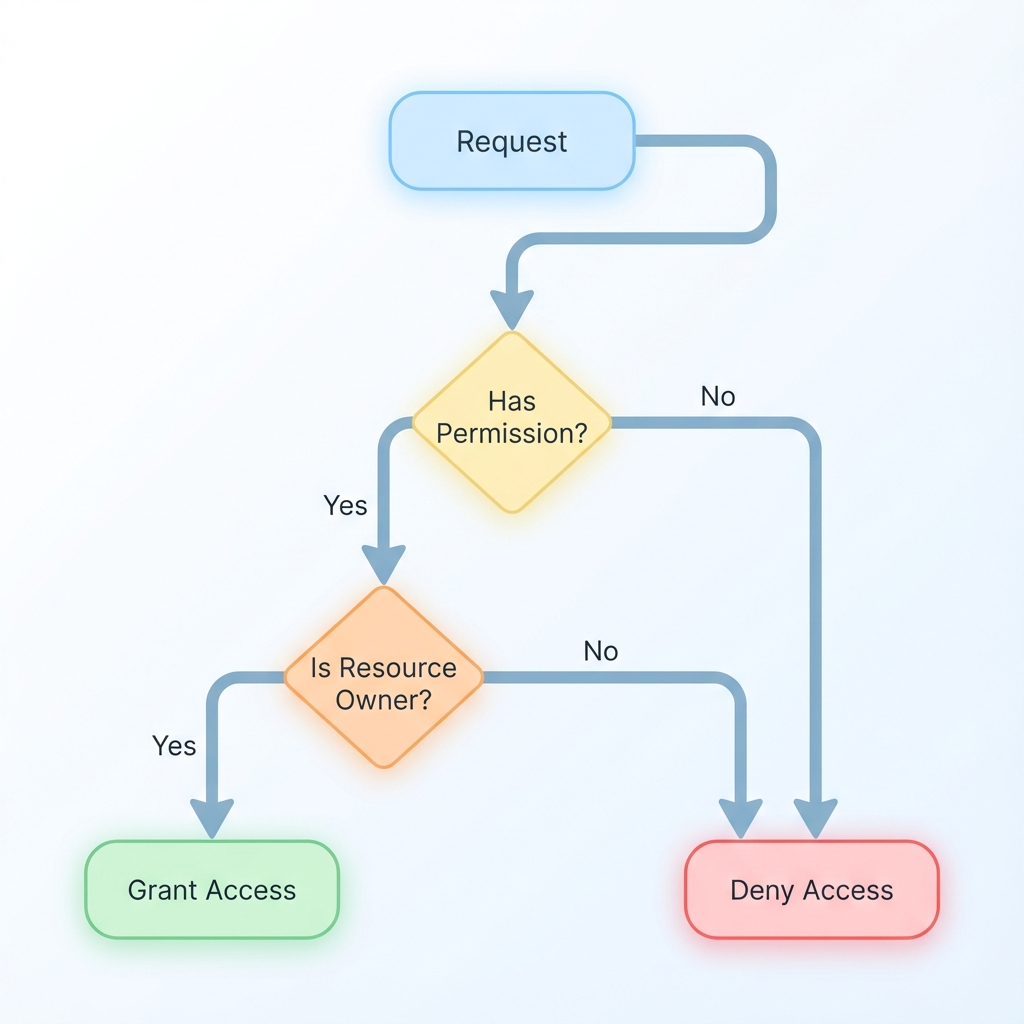

- ABAC (Attribute-Based Access Control): You can perform an action on a resource if specific attributes match. E.g., “User can edit Post IF user.id == post.authorId.”

Implementing ABAC requires a shift in thinking. We stop asking “Is this user an Admin?” and start asking “Does this user have the ability to update this specific Article?”

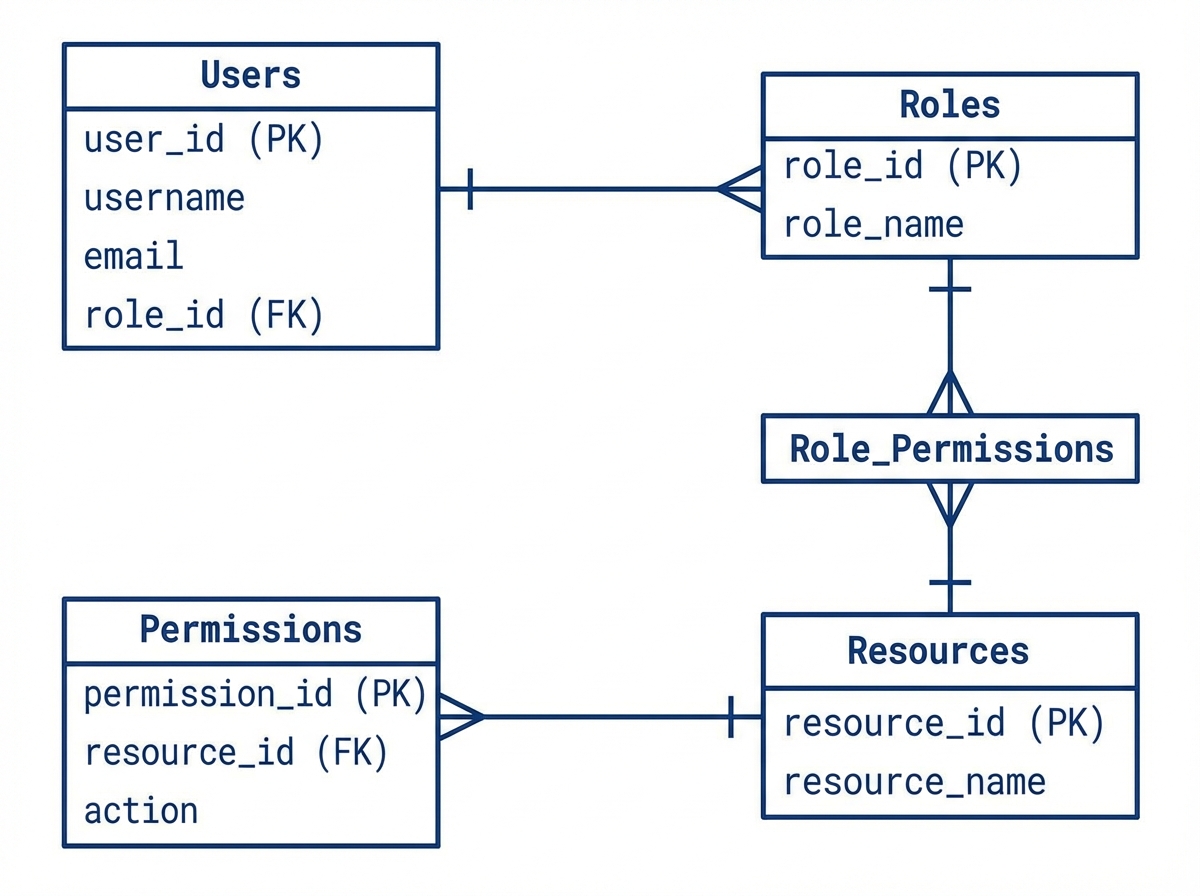

Database Schema Design for Dynamic Permissions

Hardcoding roles in your code (const ROLES = ['admin', 'user']) is an anti-pattern for enterprise systems. If a business requirement changes, you shouldn’t have to redeploy your API. Permissions should be data.

We need a normalized schema that supports:

- Roles: Containers for permissions.

- Permissions: Granular rules (Action + Subject).

- Inheritance: The ability for an Admin to inherit all User permissions.

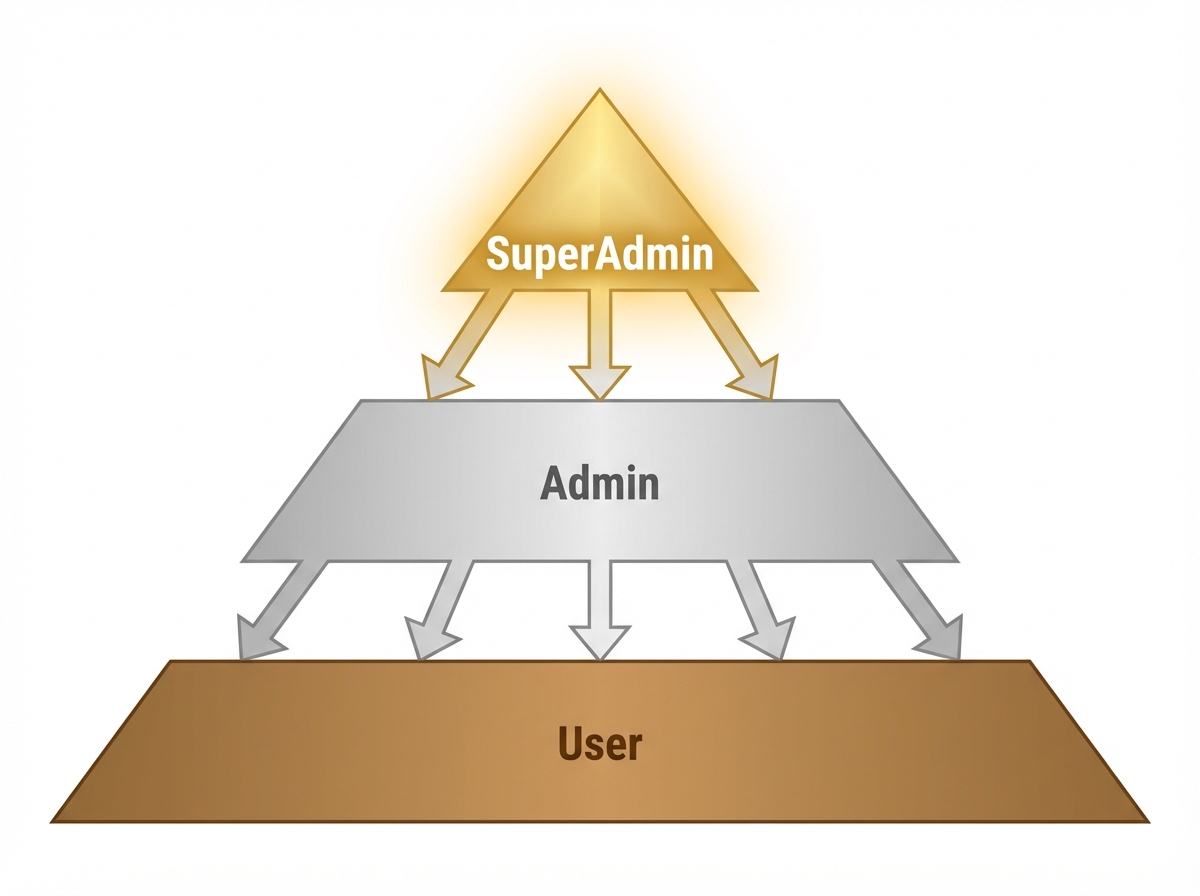

The Hierarchy Problem

In a simple system, roles are flat. in a real system, roles are hierarchical. A SuperAdmin should implicitly have all permissions of an Admin, who has all permissions of a Moderator.

The Schema (Prisma Example)

Here is a schema designed for flexibility. It allows roles to be defined dynamically and supports complex inheritance through a self-referencing relation (or an adjacency list pattern).

// schema.prisma

model User {

id String @id @default(uuid())

email String @unique

roleId String

role Role @relation(fields: [roleId], references: [id])

posts Post[]

}

model Role {

id String @id @default(uuid())

name String @unique // e.g., "editor", "admin"

description String?

// Implicit inheritance handling

parentId String?

parent Role? @relation("RoleHierarchy", fields: [parentId], references: [id])

children Role[] @relation("RoleHierarchy")

permissions Permission[]

users User[]

}

model Permission {

id String @id @default(uuid())

action String // e.g., "create", "read", "update", "delete", "manage"

subject String // e.g., "Post", "User", "Comment", "all"

// Used for ABAC conditions (stored as JSON)

// e.g., { "authorId": "${user.id}" }

conditions Json?

roleId String

role Role @relation(fields: [roleId], references: [id])

}

model Post {

id String @id @default(uuid())

title String

authorId String

author User @relation(fields: [authorId], references: [id])

published Boolean @default(false)

}

By storing conditions as a JSON field, we prepare our database to handle ABAC rules that can be serialized and interpreted by our application logic.

Implementing the Logic with CASL

While you can write your own permission parser, libraries like CASL (Code Access Security Logic) provide an isomorphic, battle-tested standard for defining abilities. CASL allows us to translate our database permissions into an executable function.

The Factory Pattern for Abilities

We need a factory that takes a User entity, fetches their role (and inherited roles), and constructs an Ability object.

First, let’s define the logic to flatten the role hierarchy. If a user is a SuperAdmin, we need to fetch permissions for SuperAdmin + Admin + User.

// services/auth/ability.factory.js

import { AbilityBuilder, createMongoAbility } from '@casl/ability';

import prisma from '../../utils/prisma';

/**

* Recursively fetches permissions for a role and its ancestors

*/

async function getPermissionsForRole(roleId) {

const role = await prisma.role.findUnique({

where: { id: roleId },

include: {

permissions: true,

parent: true

}

});

let permissions = [...role.permissions];

// Recursive step: if there is a parent, get their permissions too

if (role.parent) {

const parentPermissions = await getPermissionsForRole(role.parent.id);

permissions = [...permissions, ...parentPermissions];

}

return permissions;

}

/**

* Constructs the CASL Ability object for a user

*/

export async function defineAbilityFor(user) {

const { can, build } = new AbilityBuilder(createMongoAbility);

// 1. Fetch all permissions including inherited ones

const dbPermissions = await getPermissionsForRole(user.roleId);

// 2. Map DB permissions to CASL rules

dbPermissions.forEach(permission => {

let conditions = null;

// Parse dynamic conditions

// e.g., converting { "authorId": "${user.id}" } to { "authorId": 123 }

if (permission.conditions) {

const conditionString = JSON.stringify(permission.conditions);

const hydratedCondition = conditionString.replace('"${user.id}"', `"${user.id}"`);

conditions = JSON.parse(hydratedCondition);

}

if (conditions) {

// ABAC: Rule with conditions

can(permission.action, permission.subject, conditions);

} else {

// RBAC: Global rule

can(permission.action, permission.subject);

}

});

return build();

}

The Ownership Challenge (ABAC)

The hardest part of authorization isn’t blocking access—it’s conditionally allowing it. The classic scenario: “Editors can update any post, but Authors can only update their own posts.”

If we rely solely on middleware checks before the controller executes, we run into a problem: we often don’t have the resource loaded yet to check ownership.

There are two strategies here:

- Load-then-Check (Service Layer): Retrieve the record, then check permissions against it.

- Query-Injection (Database Layer): Modify the database query to only return records the user is allowed to see.

For high performance, Query-Injection is superior for READ operations (filtering lists), while Load-then-Check is necessary for UPDATE/DELETE operations.

Strategy: Use CASL to Generate Database Queries

CASL integrates with ORMs like Mongoose and Prisma (via accessibleBy). This translates permissions into WHERE clauses.

// services/post.service.js

import { accessibleBy } from '@casl/prisma';

async function listPosts(userAbility) {

// Instead of fetching all and filtering in memory (BAD performance),

// we push the logic down to the database.

const posts = await prisma.post.findMany({

where: accessibleBy(userAbility).Post

});

return posts;

}

If the user is an Author, CASL automatically injects WHERE authorId = 'user_id'. If they are an Admin with a “manage all” permission, the WHERE clause is omitted.

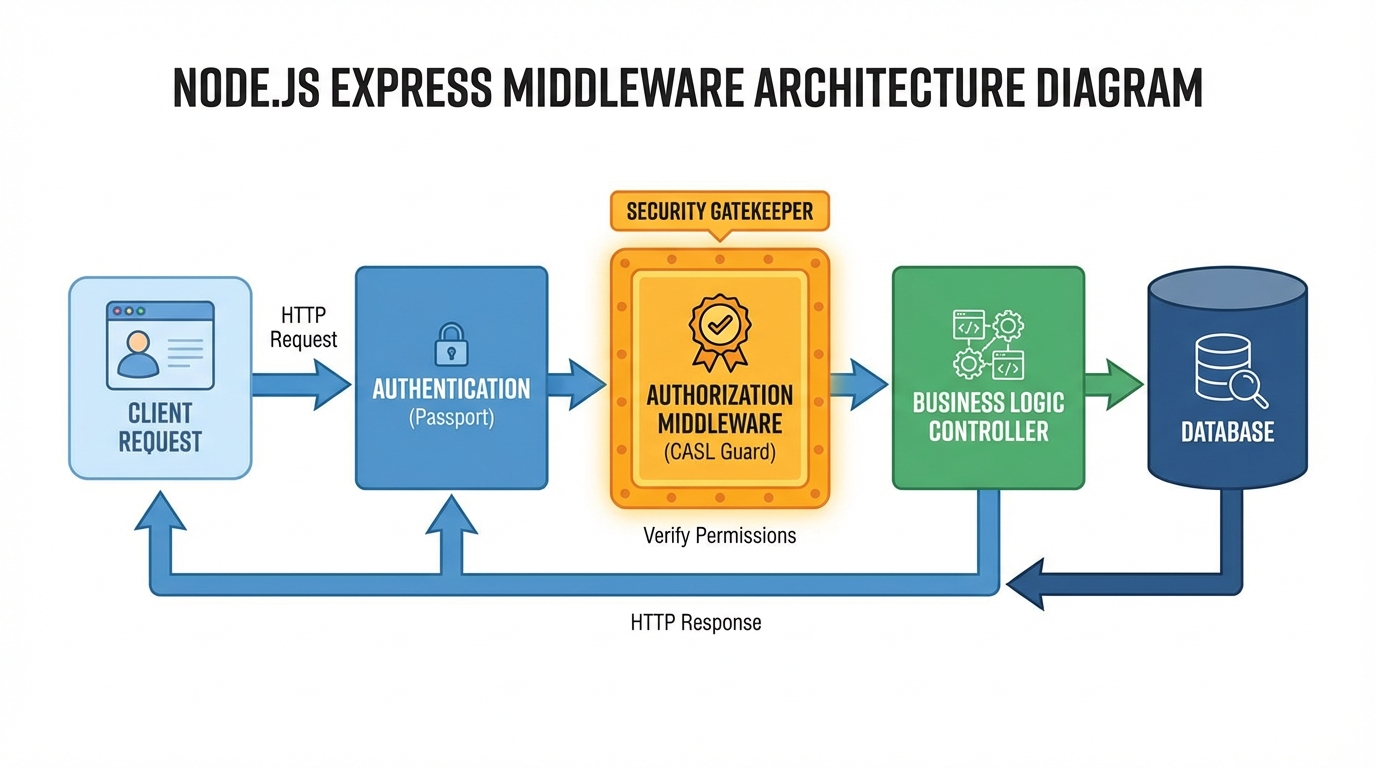

Architecture: The Reusable Middleware

We want our controllers to be clean. They should not know about role hierarchies or JSON conditions. We implement a middleware that accepts the “Intent.”

// middleware/authorize.js

import { defineAbilityFor } from '../services/auth/ability.factory';

import { ForbiddenError } from '../utils/errors';

export const authorize = (action, subjectType) => {

return async (req, res, next) => {

try {

// 1. Construct Ability (assuming user is attached to req by auth middleware)

const ability = await defineAbilityFor(req.user);

// 2. Check Global Access (RBAC check)

// This checks if the user generally has access to this Subject type

if (!ability.can(action, subjectType)) {

throw new ForbiddenError(`You are not allowed to ${action} ${subjectType}`);

}

// 3. Attach ability to request for context-aware checks later

// (Required for specific ownership checks in the controller/service)

req.ability = ability;

next();

} catch (error) {

next(error);

}

};

};

Usage in Routes:

// routes/post.routes.js

import { authorize } from '../middleware/authorize';

// Anyone with 'read' on 'Post' can access

router.get('/', authorize('read', 'Post'), PostController.index);

// Anyone with 'create' on 'Post' can access

router.post('/', authorize('create', 'Post'), PostController.create);

// Update is tricky: We authorize the generic intent here,

// but specific ownership check happens in the Service/Controller

router.put('/:id', authorize('update', 'Post'), PostController.update);

The Missing Link: Contextual Checks in Controller

For the PUT route, the middleware confirms the user can update posts in general. The controller confirms they can update this specific post.

// controllers/post.controller.js

import { subject } from '@casl/ability';

export const update = async (req, res, next) => {

const { id } = req.params;

const post = await prisma.post.findUnique({ where: { id } });

// ABAC Check: Does the rule match THIS specific document instance?

// If user is Author, this checks: post.authorId === user.id

if (!req.ability.can('update', subject('Post', post))) {

return res.status(403).json({ error: "You cannot update this post" });

}

// Proceed with update...

};

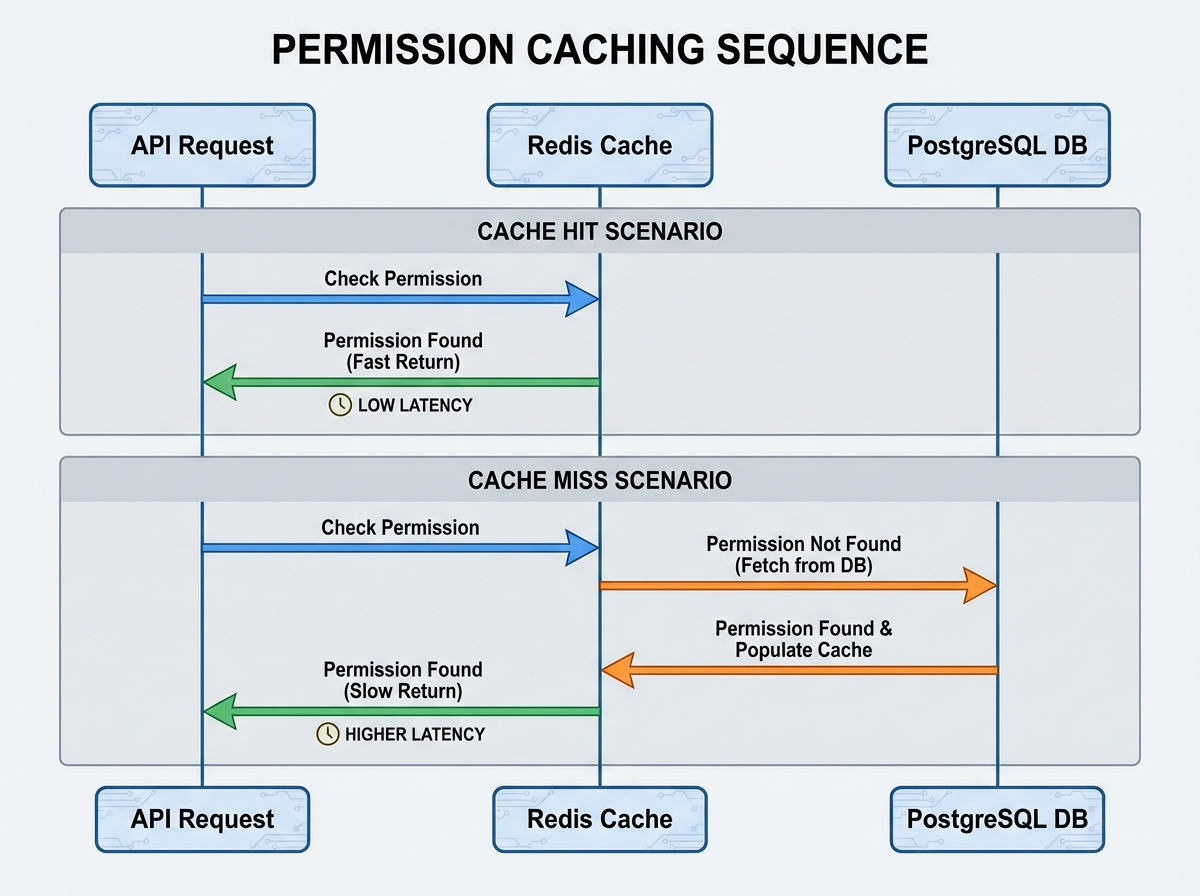

Performance Optimization: Caching Permissions

In the architecture above, defineAbilityFor(req.user) hits the database to fetch roles and permissions on every request. For a high-traffic API, this is a bottleneck.

We need to implement a caching layer using Redis. However, we cannot simply cache the Ability object because it contains functions. Instead, we cache the Raw Rules (JSON).

Redis Implementation

- Key Generation:

auth:permissions:${userId}. - TTL: Set a reasonable expiry (e.g., 10 minutes) or use event-driven invalidation.

// services/auth/ability.factory.js (Optimized)

import redis from '../../utils/redis';

export async function defineAbilityFor(user) {

const cacheKey = `auth:rules:${user.id}`;

// 1. Try to fetch raw rules from Redis

const cachedRules = await redis.get(cacheKey);

if (cachedRules) {

// Rehydrate ability from JSON rules

return new AbilityBuilder(createMongoAbility).build({

conditionsMatcher: lambdaMatcher // logic to handle conditions

}, JSON.parse(cachedRules));

}

// 2. Cache Miss: Fetch from DB (same logic as before)

const dbPermissions = await getPermissionsForRole(user.roleId);

// Convert DB permissions to CASL Rule Objects

const rules = dbPermissions.map(p => ({

action: p.action,

subject: p.subject,

conditions: parseConditions(p.conditions, user)

}));

// 3. Store rules in Redis

await redis.set(cacheKey, JSON.stringify(rules), 'EX', 600); // 10 mins

return createMongoAbility(rules);

}

Invalidation Strategy

The cache must be invalidated whenever:

- A User’s role changes.

- A Role’s permissions are modified.

- The Role hierarchy structure changes.

This is best handled via an event bus or direct hooks in your Role/User update services:

async function updateUserRole(userId, newRoleId) {

await prisma.user.update({ ... });

await redis.del(`auth:rules:${userId}`); // Force refresh on next request

}

Handling Edge Cases & Advanced Scenarios

1. Field-Level Security

Sometimes a user can update a resource, but not all fields of that resource. For example, a User can update their bio, but not their subscriptionStatus.

CASL supports this via the fields property.

// Permission in DB

{

"action": "update",

"subject": "User",

"fields": ["bio", "avatar", "name"], // Explicit whitelist

"conditions": { "id": "${user.id}" }

}

In your controller, you filter the request body using libraries like lodash.pick based on permitted fields from req.ability.

2. Multi-Tenancy

If your app is multi-tenant (e.g., SaaS), roles are often scoped to an Organization.

The schema must evolve: UserRoles table linking User, Role, and Organization.

The middleware logic changes slightly:

- Determine the

OrganizationIDfrom the request (header or param). - Fetch the user’s role for that specific organization.

- Build the Ability.

Conclusion

Moving away from if (isAdmin) is not just about cleaning up code; it is about decoupling policy from implementation. By treating permissions as data, utilizing libraries like CASL for logic, and strictly enforcing access via middleware, you create a system that is secure by default.

The transition requires upfront investment in schema design and caching infrastructure, but the payoff is a system where a Product Manager can request a complex new role hierarchy, and you can implement it without rewriting a single line of controller code.

Key Takeaways:

- Database: Store roles and permissions in the DB, not code.

- Logic: Use CASL to handle rule complexity and ownership checks.

- Architecture: Decouple authorization checks into middleware (Action/Subject).

- Performance: Cache the compiled rules (JSON) in Redis, not the evaluation logic.

Secure your applications now, before the boolean flags bury you.