Beyond GET and SET: Architecting Resilient Distributed Caching Patterns for Microservices

Introduction

In the infancy of a backend application, caching is often treated as a simple key-value store optimization—a sprinkle of “magic dust” to speed up slow SQL queries. Developers implement a basic client.get() and client.set(), push to production, and watch latencies drop. It feels victorious.

However, as traffic scales and the architecture fractures into microservices, this naive approach becomes a ticking time bomb. In distributed systems, a cache is not just a performance booster; it is a critical component of system stability. When used incorrectly, a cache becomes a source of non-deterministic bugs, data inconsistency, and catastrophic cascading failures.

The difference between a junior implementation and a senior architect’s design lies in how the system behaves when things go wrong. What happens when the cache cluster nodes flap? What happens when a marketing push expires 10 million keys at the exact same second? How do you maintain read-your-own-write consistency across distributed nodes?

This post dives deep into the architecture of resilient caching. We will move beyond simple storage and explore robust topologies, mitigation strategies for reliability failures, and advanced sharding techniques.

Caching Topologies & Patterns

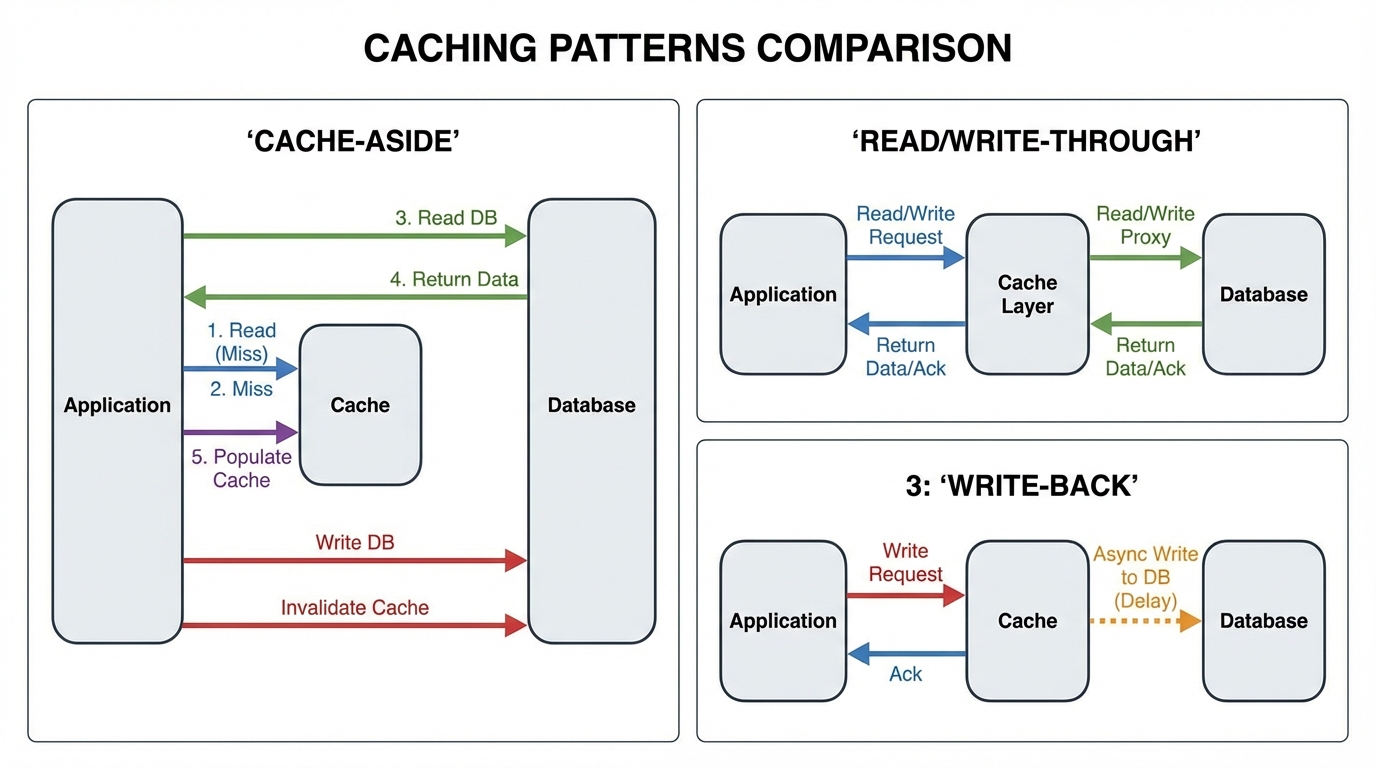

Choosing the right caching pattern dictates how your application interacts with the data store. There is no “one size fits all”; the choice depends heavily on your read/write ratio and consistency requirements.

1. Cache-Aside (Lazy Loading)

This is the most common pattern in distributed systems. The application code (the side) is responsible for orchestrating the data flow.

- Flow: The app checks the cache. If it hits, return data. If it misses, the app queries the database, updates the cache, and returns the data.

- Pros: Resilient to cache failure (the DB is the source of truth); data model in cache can differ from DB.

- Cons: “Stale data” window between DB update and cache expiry; logic clutter in application code.

2. Read-Through / Write-Through

Here, the application treats the cache as the main data store. The cache itself is responsible for fetching data from the DB or writing to it.

- Read-Through: On a miss, the cache loader fetches from the DB, caches it, and returns it.

- Write-Through: Data is written to the cache, which synchronously writes to the DB.

- Pros: Application logic is cleaner (DRY); strong consistency for reads (since cache is always updated on write).

- Cons: Higher write latency (two writes must succeed); requires a cache provider that supports custom loader logic (e.g., RedisGears or specific framework abstractions).

3. Write-Back (Write-Behind)

The application writes to the cache, and the cache acknowledges immediately. The cache then asynchronously flushes the data to the DB.

- Pros: Incredible write performance; absorbs massive write spikes (e.g., IoT sensor data, clickstreams).

- Cons: Data Loss Risk. If the cache crashes before flushing, data is gone forever.

- Use Case: Analytics counters, non-critical user interaction logs.

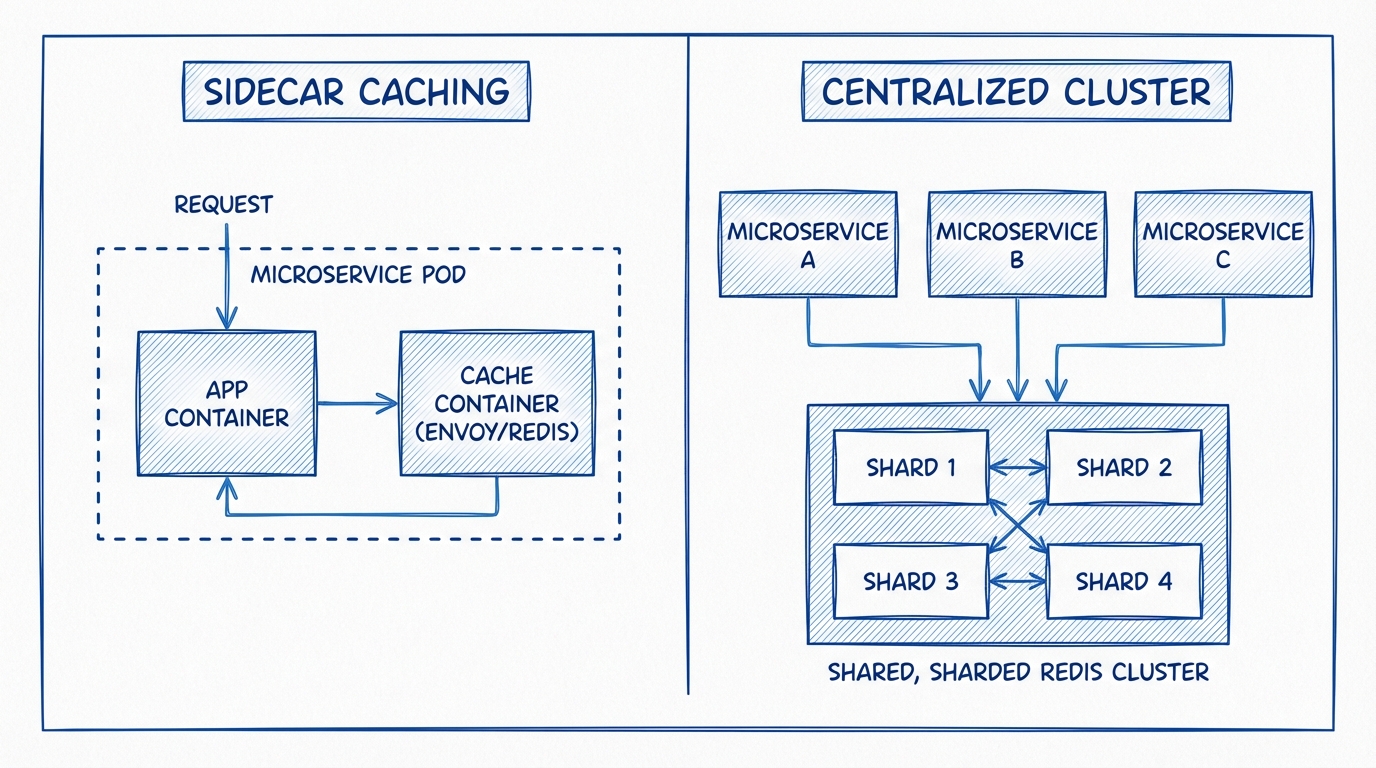

Architecture: Sidecar vs. Centralized Cluster

Where does the cache live relative to your microservices?

The Centralized Cluster (Redis/Memcached)

The traditional approach. A dedicated fleet of Redis nodes serves all microservices.

- Pros: Shared state across all service instances; independent scaling of compute (app) and memory (cache).

- Cons: Network latency (serialization + wire time); potential for “Noisy Neighbor” issues if multiple services share the same cluster.

The Sidecar Topology

With the rise of Service Meshes (Istio, Linkerd) and Dapr, the sidecar pattern places a cache instance (like a small Redis process or Envoy filter) on the same network namespace or pod as the application container.

- Pros: Sub-millisecond latency (loopback interface); isolation (Service A’s cache load doesn’t affect Service B).

- Cons: Cache fragmentation (low hit rates if requests are load-balanced randomly across pods); difficult to maintain consistency across sidecars; memory overhead per pod.

Verdict: Use a Centralized Cluster for shared entity data (User Profiles, Product Catalog). Use Sidecars for ephemeral, service-specific configuration or highly transient session state where consistency is less critical than raw speed.

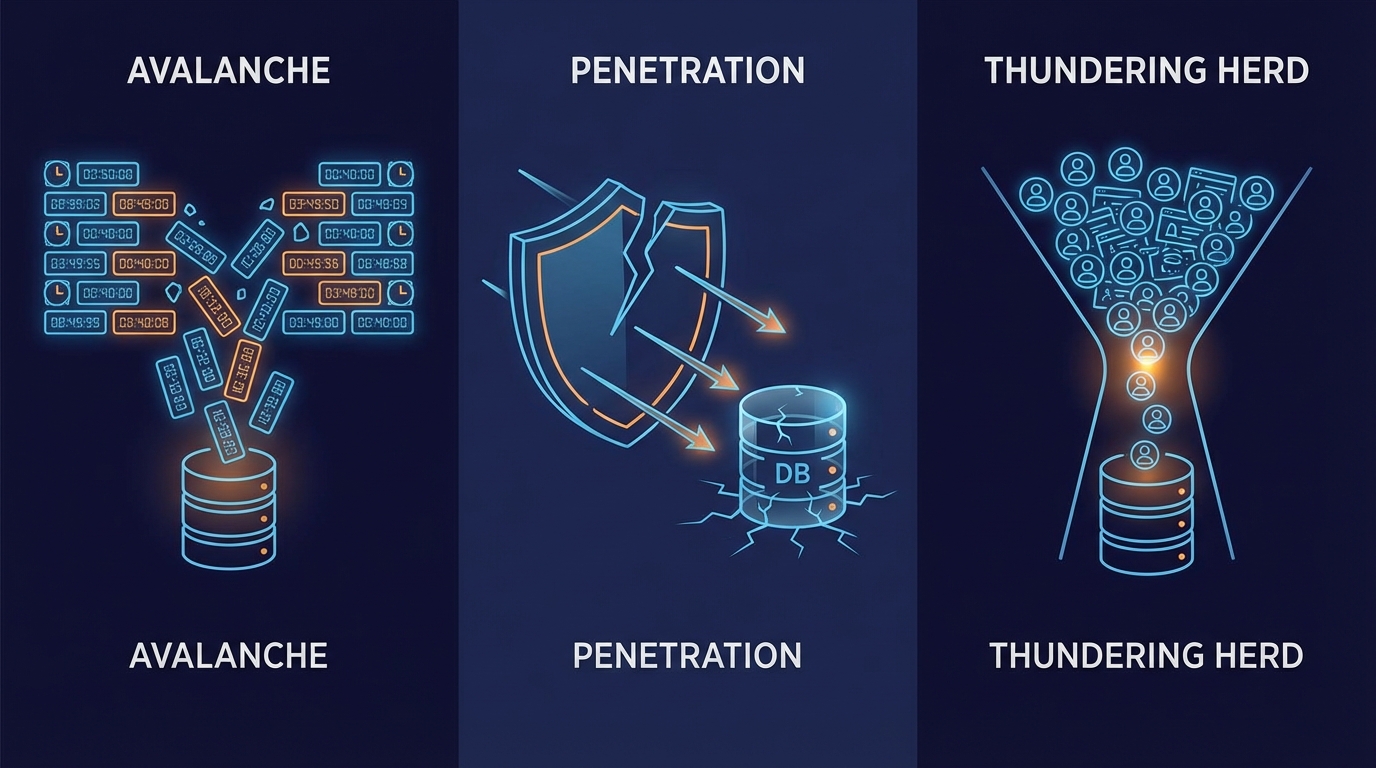

The “Big Three” Reliability Failures

In high-throughput systems, the way your cache handles expiry and misses determines whether your database survives peak load. We must architecturally defend against the “Big Three.”

1. Cache Avalanche

The Scenario: You cache 10,000 product details, all with a TTL of 60 minutes. At 12:00 PM, you deploy. At 1:00 PM, all 10,000 keys expire simultaneously. Your database is instantly hammered by thousands of reconstruction queries.

The Solution: TTL Jitter. Never use a hardcoded TTL. Always add a random variance.

import random

def set_product_cache(product_id, data):

base_ttl = 3600 # 60 minutes

# Add +/- 10% jitter

jitter = random.randint(-360, 360)

final_ttl = base_ttl + jitter

redis_client.setex(f"product:{product_id}", final_ttl, data)

By spreading the expiry, you smooth out the re-computation load on the database, turning a spike into a manageable curve.

2. Cache Penetration

The Scenario: A malicious actor (or a buggy crawler) requests IDs that do not exist in your database (e.g., id=-1 or UUIDs that aren’t real). The cache misses, the DB is queried, returns nothing, and nothing is cached. The attack continues, effectively DoS-ing your database.

The Solution: Bloom Filters and Null Caching.

Strategy A: Cache Nulls. If the DB returns nothing, cache a “Null Object” with a short TTL (e.g., 5 minutes).

def get_user(user_id):

cache_key = f"user:{user_id}"

data = redis_client.get(cache_key)

if data == "NULL":

return None # Hit on a known non-existent key

if data:

return deserialize(data)

# DB Lookup

user = db.find_user(user_id)

if not user:

# Cache the negative result for a short time

redis_client.setex(cache_key, 300, "NULL")

return None

redis_client.setex(cache_key, 3600, serialize(user))

return user

Strategy B: Bloom Filters. Before even hitting Redis, check a Bloom Filter (a probabilistic data structure). If the Bloom Filter says the key definitely doesn’t exist, reject the request immediately.

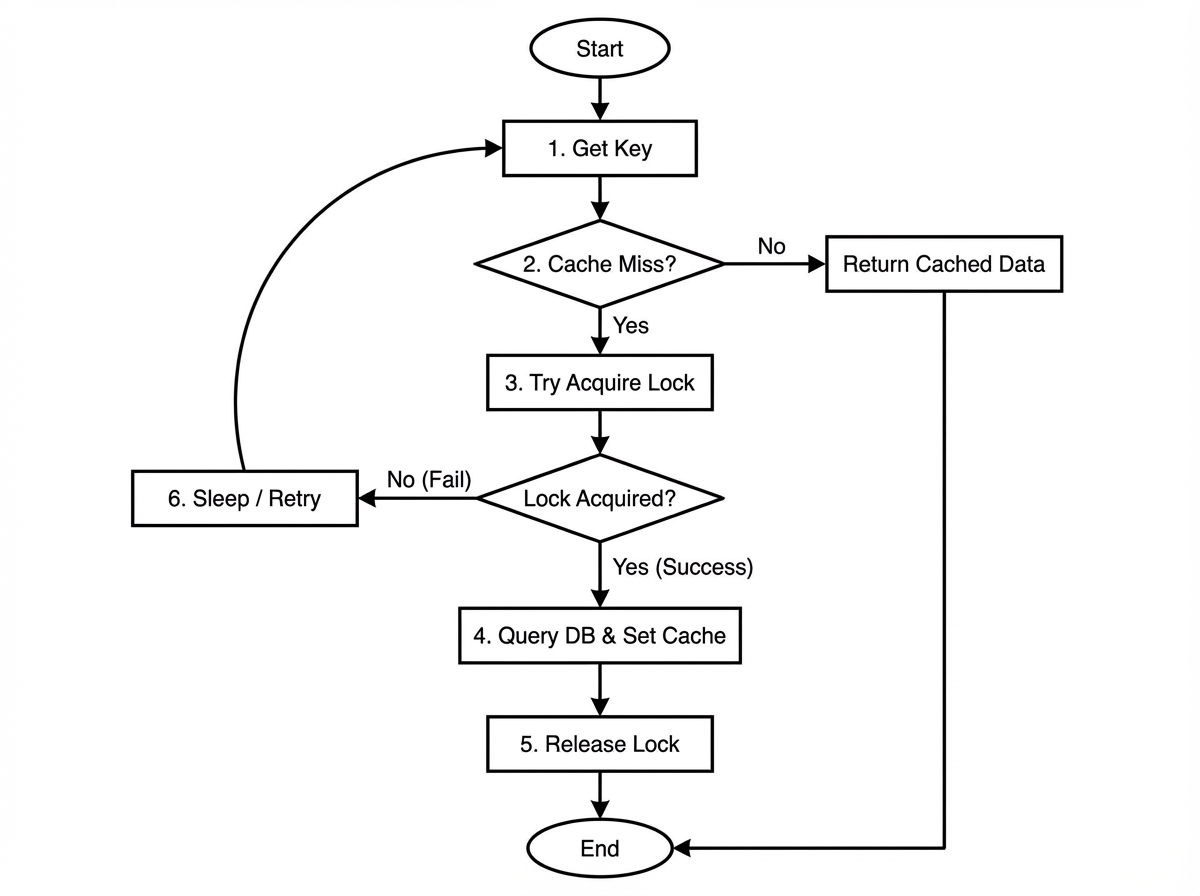

3. Cache Breakdown (Thundering Herd)

The Scenario: A single key (e.g., “Homepage_Top_News”) is extremely hot (10k req/sec). The key expires. Instantly, 10,000 requests hit the cache, miss, and all 10,000 rush to the database to calculate the same value.

The Solution: Mutex Locking (Check-Lock-Check). Only allow ONE thread/process to rebuild the cache. Everyone else waits or receives stale data.

import time

import uuid

def get_hot_key(key):

value = redis_client.get(key)

if value:

return value

# Key missed. Acquire distributed lock.

lock_key = f"lock:{key}"

token = str(uuid.uuid4())

# Try to acquire lock with 10s timeout to prevent deadlocks

if redis_client.set(lock_key, token, nx=True, ex=10):

try:

# Recheck cache just in case another thread finished

# while we were waiting for the lock

value = redis_client.get(key)

if value:

return value

# I am the chosen one. Query DB.

value = db_query(key)

redis_client.setex(key, 3600, value)

return value

finally:

# Release lock safely using Lua script (omitted for brevity)

if redis_client.get(lock_key) == token:

redis_client.delete(lock_key)

else:

# Failed to get lock. Sleep and retry (or return stale if architecture allows)

time.sleep(0.1)

return get_hot_key(key)

Consistency vs. Availability: The Hard Truths

There are only two hard things in Computer Science: cache invalidation and naming things. In microservices, Strong Consistency with caching is essentially impossible without sacrificing Availability (CAP theorem).

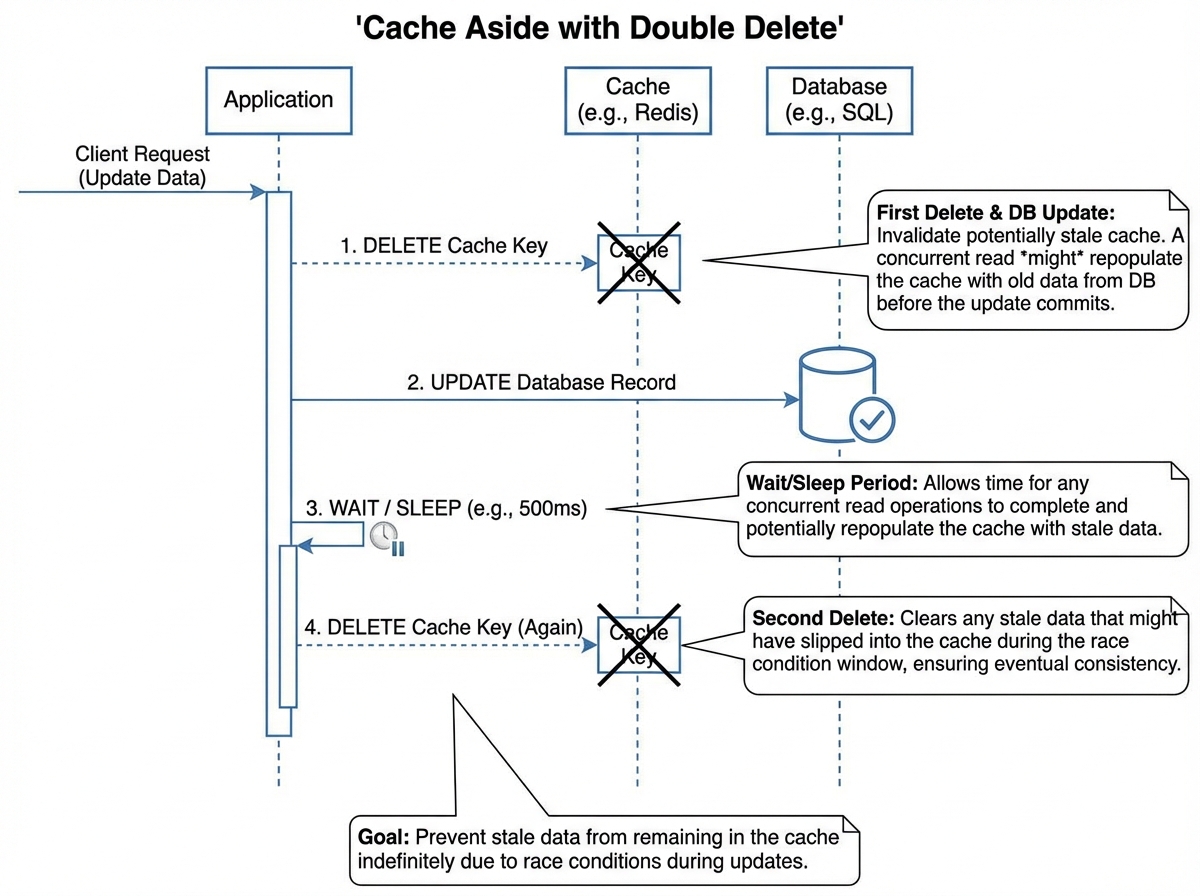

The “Double Delete” Strategy

When updating data, you have two choices: update the cache or delete the cache. Deleting is safer because updating implies you know the exact final state, which might be complex due to serialization.

However, a simple db.update(); cache.delete(); is flawed.

- Thread A updates DB.

- Thread A deletes Cache.

- Thread B reads DB (which might still be returning old data due to replication lag).

- Thread B repopulates Cache with old data.

- Cache is now permanently stale.

Solution: Delayed Double Delete.

- Delete Cache.

- Update Database.

- Sleep (Wait for DB replication lag, e.g., 500ms).

- Delete Cache Again.

This ensures that any read that occurred during the race condition is flushed out.

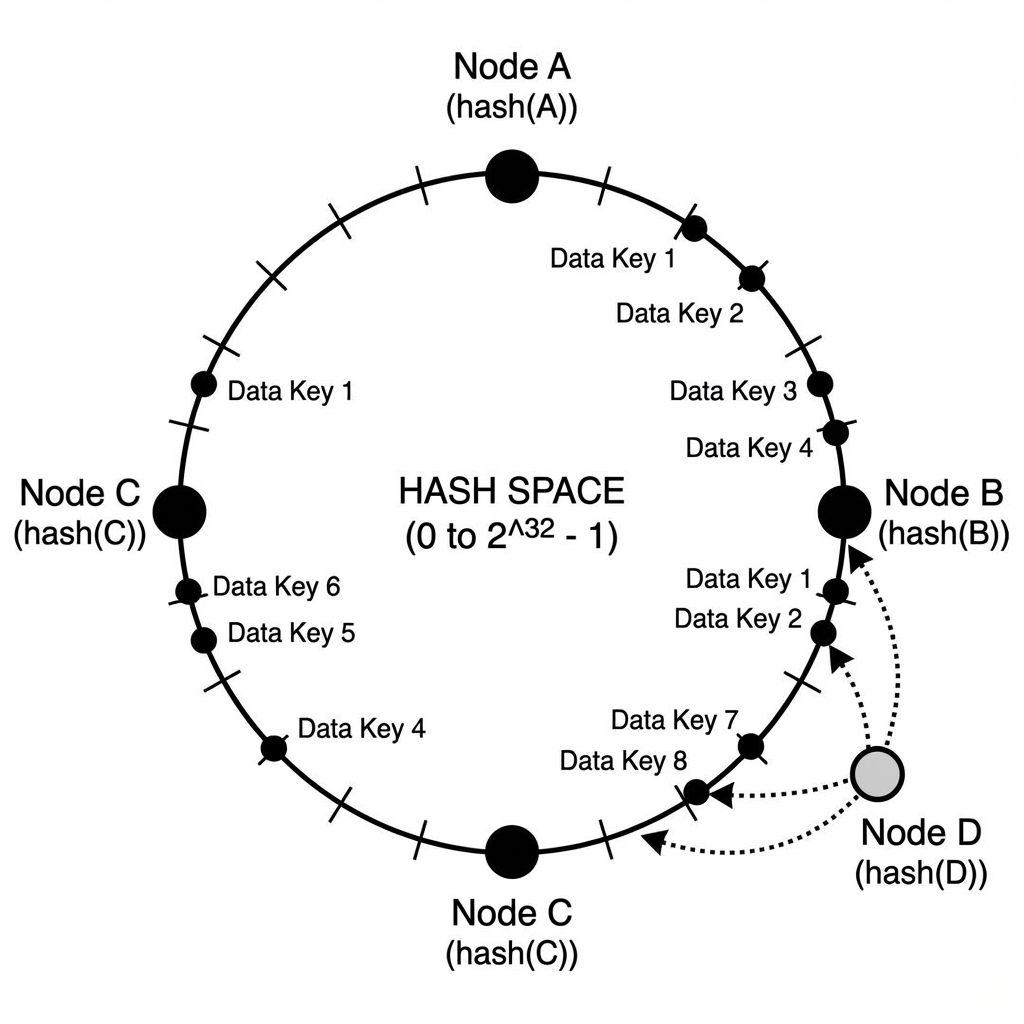

Advanced Sharding: Consistent Hashing

When you scale Redis beyond a single node, you need to shard keys. The naive approach is Modulo Hashing:

Node = hash(key) % N (where N is number of nodes).

The Problem: If you add a node (N becomes N+1), the result of the modulo changes for almost every key. 100% of your cache is invalidated instantly. This is a cache apocalypse.

The Solution: Consistent Hashing (Ring Topology). Imagine a circle (Ring) representing the hash space (0 to 2^32).

- Place your Server Nodes at points on the ring based on

hash(ServerIP). - Place your Keys on the ring based on

hash(Key). - To find the node for a key, move clockwise on the ring until you hit a server.

Virtual Nodes:

If you have few nodes, the distribution on the ring might be uneven (Node A gets 80% of data). We create “Virtual Nodes.” Node A exists on the ring as NodeA_1, NodeA_2… NodeA_100. This statistically ensures uniform distribution.

When a node is added or removed, only the keys falling into that specific segment of the ring are affected (roughly 1/N of the keys). This allows elastic scaling without flushing the cache.

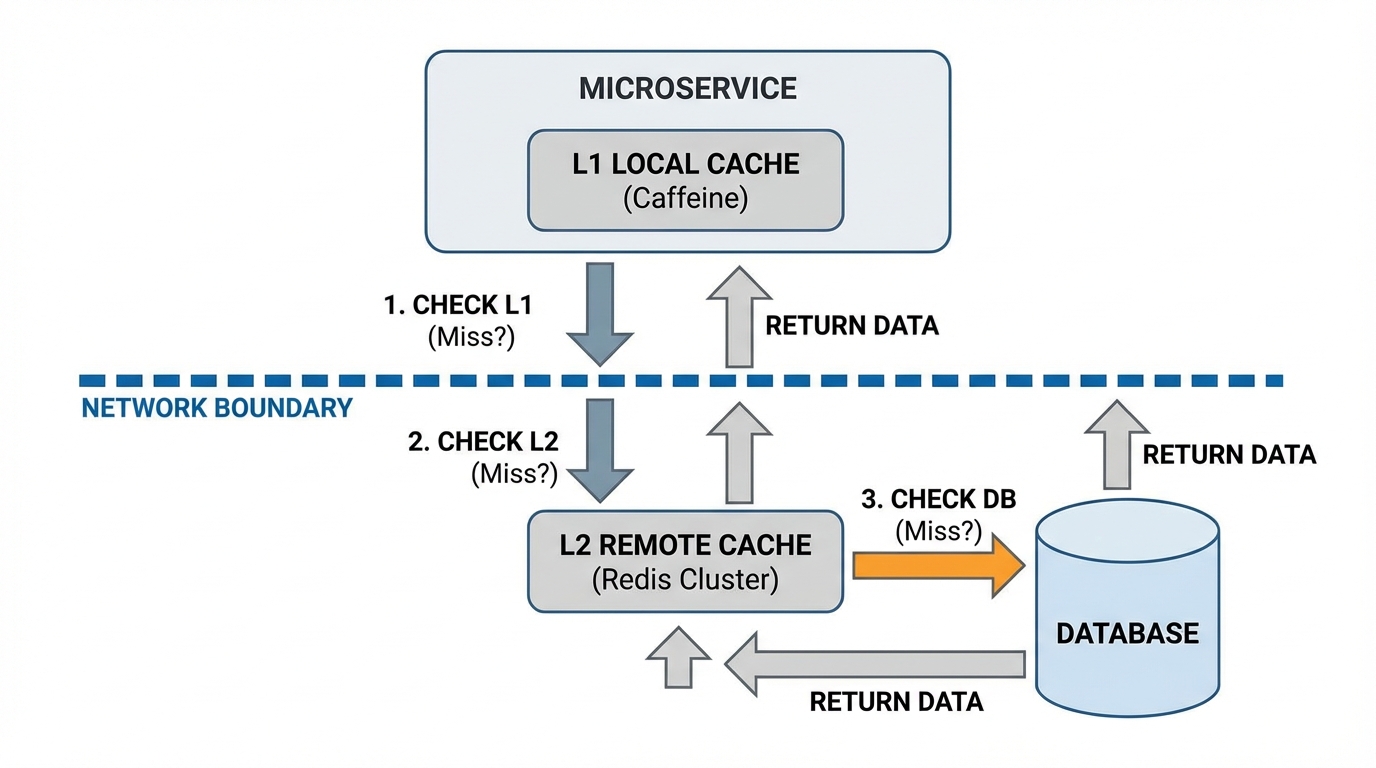

Multi-Level Caching (L1/L2) Architecture

For extreme performance requirements, a single remote Redis call (1-2ms) is too slow. You need microseconds. This leads to L1/L2 Caching.

- L1 (Local): In-memory cache inside the application process (e.g., Caffeine for Java, Ristretto for Go, LRU dictionary for Python). Zero network latency.

- L2 (Remote): Redis Cluster. Shared state.

The Synchronization Problem

If Instance A updates a user in DB and invalidates its L1 and the shared L2, Instance B still has the old user in its L1.

The Solution: Pub/Sub Invalidation. We use Redis Pub/Sub as a notification channel.

- Read Path: Check L1 -> Check L2 -> Check DB -> Populate L2 -> Populate L1.

- Write Path:

- Update DB.

- Delete L2 Key.

- Publish message to Redis Channel

cache-invalidation:{"key": "user:123"}. - All service instances subscribe to this channel. Upon receiving the message, they evict

user:123from their local L1.

Implementation Logic (Pseudo-code):

# Application Startup

def start_subscriber():

pubsub = redis_client.pubsub()

pubsub.subscribe('cache-invalidation')

for message in pubsub.listen():

if message['type'] == 'message':

key_to_delete = message['data']

local_cache.invalidate(key_to_delete)

# Write Operation

def update_data(key, value):

db.update(key, value)

redis_client.delete(key) # Clear L2

# Notify all L1s to clear

redis_client.publish('cache-invalidation', key)

This architecture provides the speed of local memory with the consistency controls of a distributed system.

Conclusion

Architecting distributed caching is an exercise in managing failure modes. It requires shifting your mindset from “Caching is a storage feature” to “Caching is a distributed systems problem.”

To build resilient systems:

- Assume failure: Design for the empty cache scenario (Avalanche protection).

- Defend the DB: Use Bloom filters and locking to prevent Thundering Herds.

- Respect Physics: Understand that strong consistency across distributed nodes incurs a latency penalty.

- Layer intelligently: Use L1/L2 caching when network hops become the bottleneck, but automate the invalidation.

The goal isn’t just a high cache hit ratio; it’s a system that degrades gracefully, scales elastically, and remains consistent enough for the business logic to hold true.